Abstract

Increasing competition in the business environment with the effect of globalization has led investors who want to increase their profits to try different ways. For this reason, share ownership has emerged in different companies in the same market. These complicated structures, which are called common ownership, are not considered a merger/acquisition or a cartel within the framework of current competition law regulations. However, the acquisition of minority shares in rival companies by institutional investors threatens competition due to the common control it provides in the market. Common control, on the other hand, means shareholder activism, since it is realized through the interventions of the shareholders in the company management. With this course of action, competition in the market will be softened and the profit to be obtained will be maximized. Recent studies in the literature show that investors holding minority stakes in more than one competitor can influence the management decisions of the firms. This article will examine the effects of common ownership by institutional investors on competition.

Keywords: Institutional Investors, Minority Shareholders, Competition, Common Ownership, Control, Common Market, Shareholder Activism

Özet

Küreselleşmenin etkisiyle iş ortamında artan rekabet, kârını artırmak isteyen yatırımcıları farklı yollar denemeye yöneltmiştir. Bu nedenle aynı pazarda farklı şirketlerde pay sahipliği ortaya çıkmıştır. Ortak mülkiyet olarak adlandırılan bu karmaşık yapılar, mevcut rekabet hukuku düzenlemeleri çerçevesinde bir birleşme/devralma veya kartel olarak değerlendirilmemektedir. Ancak kurumsal yatırımcıların rakip şirketlerdeki azınlık hisselerini satın alması, piyasada sağladığı ortak kontrol nedeniyle rekabeti tehdit etmektedir. Ortak kontrol ise, hissedarların şirket yönetimine müdahaleleri ile gerçekleştiğinden, hissedar aktivizmi anlamına gelir. Bu hareket tarzı ile piyasadaki rekabet yumuşatılacak ve elde edilecek kâr maksimize edilecektir. Literatürdeki son araştırmalar, birden fazla rakipte azınlık hissesine sahip yatırımcıların firmaların yönetim kararlarını etkileyebileceğini göstermektedir. Bu makale, kurumsal yatırımcıların ortak mülkiyetinin rekabet üzerindeki etkilerini inceleyecektir.

Anahtar Kelimeler: Kurumsal Yatırımcılar, Azınlık Pay Sahipleri, Rekabet, Ortak Mülkiyet, Kontrol, Ortak Pazar, Pay Sahibi Aktivizmi

Introduction

The way investors act in the global market is changing day by day. Investors who do not want to undertake all the risks by holding their shares in a single company, diversify their assets and take actions to both protect themselves from risks and provide sector-based control. On the other hand, these actions of investors present competition law with a new problem these days.

This problem is that institutional investors gain control over company management through horizontal shareholding and it threatens competition. This situation is based on minority shares and it has not been subject to legal regulation because it is difficult to reveal due to its complex structure. However, in recent days, empirical studies, especially in the USA, have revealed the situation clearly and practices that violate competition have begun to be detected.

The basic starting point of the problem is explained as follows; Institutional investors, who hold minority shares of many companies in the same market, reduce competition by interfering with the management of these companies, thus tending to increase profitability in the sector. The issue is also related to shareholder activism in one aspect. Because the shareholders, who are not satisfied with the profitability of the company, that is, they think that it is not managed well, interfere with the management in various ways. Even more, the intervention by the horizontal shareholders in the companies in the same market does not occur in a single company; it means intervention in the management of more than one company. In a broad sense, it is to take control of the sector.

The reason why this structure called common ownership, is preferred is that the cartel formed by non-competing companies in the sector maximizes the profit in that market. In other words, this means a collective action, and instead of increasing the profit of a single company by investing in only one company, the investor invests in more than one company in the same sector and maximizes the profit. This provides common control in the market and reduces competition. Empirical studies, especially in the airline sector in the USA and the banking sector in Europe, have revealed this situation.

In this study, the realization of common ownership, and its violating aspect of competition, will be explained and evaluations will be made. In the first part, the concept of institutional investor and common ownership will be discussed and how common ownership is realized by institutional investors will be explained. In the second part, common ownership will be evaluated as shareholder activism. In addition, shareholder activism, the rights of minority shareholders, and their effects on company management will be explained in this section. In the last part, the situation of minority shareholders in the face of current competition regulations will be discussed and their effects on competition will be discussed.

1. Institutional Investors and Common Ownership

Since common ownership and investments can be realized in different ways, it will briefly touch on these concepts and then explain the joint venture type that is the subject of our study.

1.1 Institutional Investors

Institutional shareholders are financial institutions that specialize in collecting individual investors' savings in a pool, evaluating these savings with financial and non-financial instruments, asset management and obtaining maximum profit from these investments[1]. They provide funds to the market with the money saved by institutional investors. These funds include funds such as pensions, insurance companies, banks.[2]

Institutional shareholders may have a direct or indirect relationship with the corporate they invest in. This means that the institutional shareholder can manage the investment portfolio himself or leave it to asset managers. In the first case they are in direct relation; in the second case their relation is indirect.[3]

Today, fewer and fewer investors hold their shares directly. Instead, investors are turning to fund units that pool assets. For example: Direct ownership of stocks in the US declined from 84% in the mid-1960s to 40% in 2011. Similarly, in the United Kingdom, it fell from 54% to 11%. For example, the majority of passive index funds are managed by the “Big Three”: BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street have acquired significant stakes in thousands of publicly traded companies, both in the US and internationally.[4]

The main aim of investors is to make a profit. By distributing their shares among different funds, they aim to protect their investments from the risks that may arise within a single share and a single company. Besides, mutual funds pool capital from different investors to buy assets or securities in bulk, thus offering a wider range of investment opportunities, risk diversity, economies of scale, and professional management expertise.[5]

1.2. Common Ownership

The concept of common ownership arises when the shares of the company owners are distributed among many companies in the same sector. This can happen in the form of individual share ownership, or it can happen when the shares owned by institutional investors and the shares of a company pass into the ownership of another company owner. For example, in the first one, a person owns shares in both airlines. In the second, the funds belonging to a company are owned by more than one share of the company in the same sector, while in the third, a company acquires the shares of another company or the companies establish a joint venture. In the second and third cases, although the shares are held by a company, the owners of these shares are different.[6]

In the above-mentioned cases, since it is accepted that control will change hands if the proportion of the shares owned is high, these ownerships are not disputed according to the competition regulations. Competition law regulations regarding these situations are available under the heading of concentrations.

The point of attention in concentration audits subject to notification is that it provides a permanent change in control and the turnover thresholds are exceeded. Our focus is on common ownership in which minority shares are owned.

1.3. Common Ownership by Institutional Investors

Common ownership refers to a situation where a third party (usually an investor) simultaneously holds minority shares in several competing companies in the same sector on the market.[7] In other words, there are 3 important elements in the form of common ownership, which is the subject of our study. These;

- holding minority shareholdings

- by institutional investors

- of several competing firms in a concentrated industry simultaneously

Figure 1. Form of common ownership in this study[8]

Example: An investor acquires a financial stake in Firm A and Firm B. If both of them are in the same industry and the investor has control in firm A, he acts according to his financial interests by considering his share in firm B.

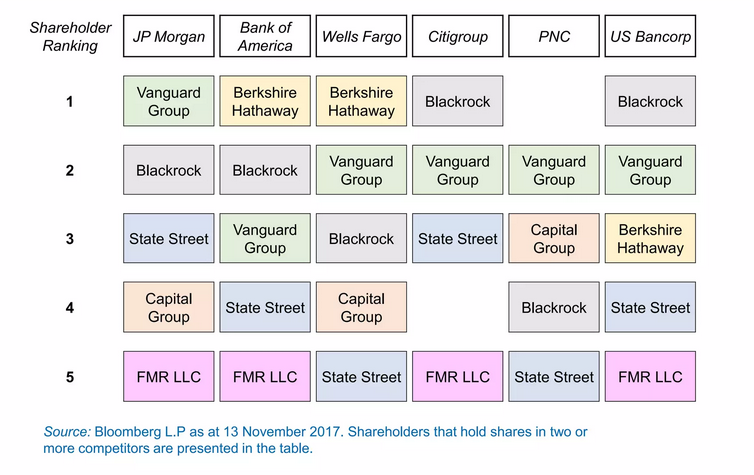

Form 2. Source Presentation by Siobhán Dennehy[9]

Several recent studies have attempted to quantify the extent of co-ownership in the United States. Although they used different methods, they generally found that the co-ownership position of U.S. public companies increased significantly, especially in certain sectors of the economy, such as airlines, banks, and soft drinks.[10]

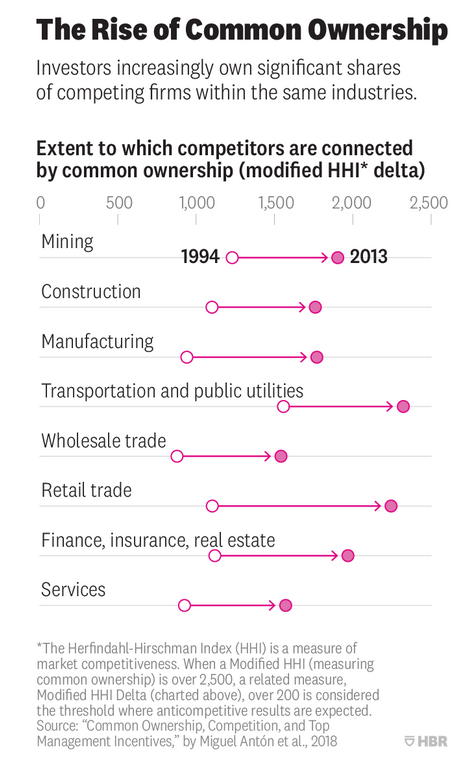

Form 3. Source Harvard Business Review[11]

2. Common Ownership as A Kind of Shareholder Activism

It explained the common ownership of institutional shareholders who hold minority shares in the previous section. Of course, corporate shareholders have specific objectives in this partnership. For this reason, it will examine the rights of minority shareholders and the impact of the use of these rights as an example of shareholder activism in the management of the company.

2.1. Shareholder Activism

The concept of shareholder activism is a warning system where the shareholders convey their dissatisfaction with the company's policies regarding the company's financial, social and environmental performance to the company management, either by using the shareholder rights or by other means such as the media, social media, private meetings with the management, without making a fundamental change in the company's board of directors definable. In this respect, shareholders demand some changes in the management of the company in line with their own purposes. The issues that shareholders demand change cover a wide range of topics, from managers' remuneration regulations to corporate governance principles and social and environmental issues.[12]

For many years, the doctrine did not consider shareholder activism a viable option. Because, shareholders need to spend a lot of time, effort and money on activism activities, and they also need to communicate with other shareholders. For a shareholder in a multi-partner company, a more logical strategy would be for them to sell their shares, and leave the company rather than embark on shareholder activism. However, since the majority of company shares traded on the stock exchange are now in the hands of institutional shareholders rather than individual shareholders, it is argued that shareholder activism is now possible in the doctrine, that institutional shareholders can fulfill their duty of control and supervision and other shareholders will also benefit from this.[13]

From this, we can deduce that the intervention of corporate shareholders in company management can also be considered shareholding activism. The only difference in this activist movement is that interventions are not within a single company. Activist movement occurs in more than one company due to institutional investors holding shares in more than one competitor company. Although this activism seems to occur in the shares of a single corporate shareholder in different companies, it actually occurs as a collective action due to the diversity of the actual owners of these shares. Also, this movement does not only affect the management of a single company, but also the management of a specific sector in the market.

2.2. Minority Shareholders Rights in Turkish Commercial Code

According to the Turkish Commercial Code[14], minority shareholders are shareholders who hold at least one tenth of the capital (one twentieth of the capital in publicly traded companies).[15]

Minority shareholder rights can be divided into positive and negative minority rights. In negative minority rights, the minority can block compromise and release by voting negatively. Regarding positive rights, the minority benefits from the rights granted to itself by the TCC by voting affirmatively. Positive minority rights can be shown as the right to request a lawsuit against the board of directors and request to include certain items on the agenda.[16]

Minority rights in the code do not give the minority control over an enterprise. However, the rights granted to the minority by the articles of association may give control over the undertaking. We will explain this subject in detail in the subsection.

2.3. Effects on Corporate Management

As a minority shareholder, it stated that the effects of corporate shareholders' rights on company management can be considered shareholding activism. However, due to the fact that these shares belong to a minority, they do not affect the management of the company, or its control, according to the legal regulations, as we mentioned in the previous heading. However, it is possible to grant certain rights to minority shareholders with the articles of association of the company. The effect on the company can be realized through these rights.

The minority may be granted various rights related to participation in management by the articles of association, without requiring the requirement of owning one-tenth of the capital specified in the law. Granted, minority rights may limit the controlling power of majority shareholders over the enterprise. With the articles of association, the minority that represents a certain percentage of the capital may be granted the right to propose a candidate for the board of directors, to veto some general assembly resolutions, or to request the dissolution of the partnership for just cause. These rights granted to the minority limit the authority of the majority. In this way, the minority can influence the management of the enterprise.[17]

3. Problem Relating to Competition

First of all, basically, summarize the situation in competition regulations. As mentioned earlier, common ownership is neither a cartel nor a merger acquisition in the literature. Therefore, by explaining the control of concentration, we can draw a general picture of the basic regulations.

Concentration transactions that are subject to notification are concentration transactions that cause permanent changes in control and transactions where turnover thresholds are exceeded. Circumstances that cause permanent changes in control are considered mergers and acquisitions and are subject to the control of concentration. These are the merger of two or more undertakings, the purchase of shares or assets of an undertaking, long-term contracts, other transactions giving rise to de facto control, and fully functional joint ventures. Since mergers and acquisitions are not considered, the situations that are not subject to concentration control are intra-group transactions, minority share purchases, transfers of control by inheritance, and situations where control is passed to the public as required by law.[18]

Within the scope of current competition regulations, like most jurisdictions, institutional investors' share purchases in different competitor companies in Turkey are not considered within the scope of mergers and acquisitions due to being a minority share. Since these minority interests do not have a significant effect on the company and do not have control power, they are not subject to merger audits.[19]

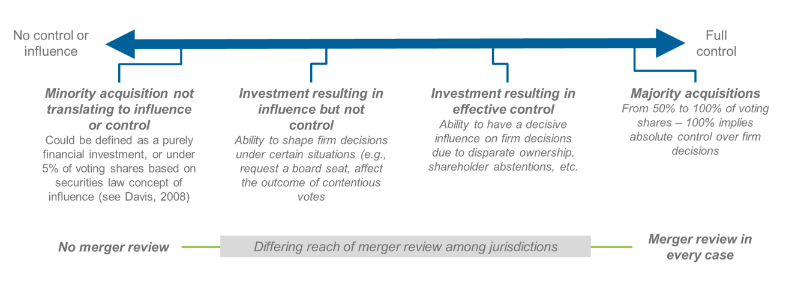

Merger audit rules are often used to examine the competitive effects of minority shareholders. To be subject to scrutiny, the concept of "control" is important. Minority shareholders are subject to a merger audit only if they cause a permanent change in control. Because only in this case can it have negative effects on competition.[20]

In this study, the focus is on institutional investors who have minority shares in competing companies. Before addressing the potential anti-competitive actions of this group, will examine the existing merger regulations for minority shareholders.

3.1. Minority Shareholdings in Merger Control

The consensus in the literature is that co-ownership among competitors in a concentrated market can reduce competition if the level of ownership is high enough. On the other hand, the competitive effects of common ownership with minority shareholders are controversial.

The antitrust literature distinguishes between controlling and non-controlling minority interests because ownership of minority interests does not in itself indicate whether the owner has the right to control or influence the target company. In the former case, minority shareholders can exercise control over the target company individually or jointly with other shareholders, while minority stakes ultimately represent purely financial participation and therefore do not have control in the legal sense.[21]

Accordingly, most merger review regimes focus on the issue of control when determining which transactions to deal with. Similarly, ownership of minority shares that do not provide control in Turkish Law is not considered within the scope of Article 2 of the Communiqué No. 1997/1 On Mergers And Acquisitions Requesting Permission From The Competition Board. However, when the minority rights recognized in the articles of association provide control over the undertaking, in this case, the acquisition of the minority shares ensures the acquisition of control over that undertaking. In this case, the takeover is considered within the scope of the Communiqué. The acquisition of control results in being subject to supervision in terms of Competition Law.[22]

Control may be created through rights that allow it to exert decisive influence over an undertaking, through contracts or in any other form. Since there is no limited counting in Article 2 of the Communiqué No. 1997/1, sample situations are regulated, it is possible to obtain control in any way other than these situations. Again, although they do not have such a right or authority, control can also be obtained by persons or undertakings who actually have the power to exercise these rights.[23]

Form 3. The diagram below shows the range of effects that can be associated with a transaction.[24]

3.2. Anticompetitive Policy

In this section, it will be discussed how the competitiveness-reducing effects of institutional investors, whose rival companies have minority shares, can be realized. This is a controversial area in the literature, and recent studies are trying to embody this effect.

3.2.1. Current Research

An article in the Harvard Business Review in 2016 showed how four mutual funds rank among the top seven shareholders of each of the four largest US airlines. Empirical studies have been carried out on a sectoral basis, especially in the United States and England. In a study conducted in Germany[25], it has been determined that corporate shareholders are concentrated[26], especially in the chemical sector.[27] This was the first time attention was drawn to this issue in the year 2018 with Symposium Innsbruck in Europe.[28] Although it has been 6 years[29] since the issue was brought to the agenda, there is no empirical study conducted on a sectoral basis in Turkey. Therefore, there are also no academic publications.

As mentioned briefly in the explanations made above, there is an effect of shares held in rival companies in the same market on the competition. First, if an investor owns more than one company in a market, it means that one company has an incentive to reduce its competition over another company. Therefore, it does not have to make an effort to lower prices or increase service per unit. Reduced competitive pressure also increases the profitability of all companies in the market. Because in the presence of competition, the unit that offers the service from the best quality to the most affordable price wins. However, since competition has decreased here, it is not necessary to play with the unit price and the price can be increased. This will increase the profits of all companies. It should be noted that in this case the effect on competition will occur spontaneously and will not require any communication with the management.[30] It is sufficient that directors serve the interests of the company's shareholders to some extent. It is almost indisputable that common ownership undermines intense competition. This is called unilateral effect.[31]

The fundamental problem is that an institutional investor cannot exert a clear influence on companies. So the question discussed is what are the ways companies can influence behaviour, even though institutional investors can't exercise effective control over their business strategy because they hold minority stakes? It can be considered these ways of creating an effect under two headings as direct effect and indirect effect. By direct effect voting, institutional investors can vote as a block. Or it can influence decisions without the need for a simple majority due to low participation of other shareholders. Indirect effect, on the other hand, may provide tacit management incentives or remain passive without making active investments and not encourage risk.[32]

In general, the effects can be listed as follows[33];

- Voice and vote

To use their votes to promote the election of board members and business strategies that lead to, or at least are consistent with, reduced competition. Institutional investors holding shares in more than one firm in the same market are likely to vote the same, thereby increasing their influence, as their incentives are closely related.

- Influence of institutional investors on the decisions of company managers

Managers' wages in large companies typically include a fixed salary plus a component that increases with the firm's profits. This type of compensation gives managers incentives to choose prices to maximize the firm's profits. If the sectoral profit is maximized, the manager gets the highest profit. (Win-win)

- Facilitating collusion between companies

Institutional shareholders can have a negative impact on competition by reducing incentives for the same minority shareholders to compete or by facilitating collusion between companies.

3.2.2. Solution Suggestions Presented in the Literature[34]

To the extent that common ownership is suspected of being associated with illegal or anti-competitive practices, public intervention will inevitably seek to identify ways to minimize or neutralize its impact. For this reason, it should be noted that this intervention should not mean narrowing fundamental shareholder rights.

Potential solutions include limiting the percentage of equity owned by an individual investor holding more than one stake in the same industry; a requirement to own only one company in a particular industry; or restricting an investor's rights to vote at General Assemblies or to associate with companies. These are among the core principles of most governance codes around the world, and challenging them is to undermine the potential of investor management and the voice of minority shareholders.

While speculative at this stage, academic proposals of this nature are viewed by most investors as grossly ill-conceived and damaging to investor goals.

Therefore, prescriptive legal attempts to address the potential anti-competitive aspects of common ownership will have other nasty side effects that are likely to be much bigger than the problem they are trying to solve.

At the moment the issue is not yet fully resolved, but competition concerns over co-ownership appear to be at least partially justified. But the real question is how important this concern is. The empirical analysis of common ownership is still in its infancy. First, a detailed assessment of how widely shared ownership is spread across different industries, or better yet, different antitrust markets, is needed. Second, empirical assessments are necessary to estimate the impact of institutional investors on competition, particularly prices. To do this, the right methods and tools must be used or developed.

Conclusion

Expanding markets as a result of globalization have increased the interest of investors. Investors did not hold their investments in a single firm and minimized the risk by owning minority shares in various firms. The preference of institutional investors for shares in rival companies attracted the attention of economists and legists. The possible effect of this shareholding, which is called common ownership in the literature, on the market has started to be the subject of research.

The fact that horizontal shareholding in the same market and in the same sector belongs to a single investor indicates that a common action style has been adopted. This movement, in a sense, corresponds to the concept of shareholder activism, which does not have a clear definition in the literature. In more than one rival company, management is intervened in a horizontal plane, with the effect to be created on the companies and the sector with a joint decision. Moreover, this intervention can create an effect that can control not only the companies, but also the entire sector in which the companies are located.

Recent studies have theorized that common ownership in rival companies may lead to a softening of competition and common control in the market. The reason for this is the opinion that firms with co-investors can avoid aggressive interventions against each other and this will result in a decrease in competition. According to economic researches, non-competition of rival firms operating in the same sector will maximize profit.

Although the studies in the literature are increasing, new empirical studies are included since they are based on similar data. Although this effect cannot be proven concretely, when numerical data are interpreted in the context of cause and effect, it is seen that the movement in the market has anti-competitive effects. For this reason, it is recommended to take some measures to limit common ownership. However, such a regulation may adversely affect investors who are minority shareholders.

Empirical studies are aimed specifically at the US and UK markets. There are also studies in Europe, especially in Germany. However, no empirical studies have been conducted on the Turkish market. Neither concretizing the theories about how common ownership violates competition regulations, nor there aren't enough empirical studies on the concentration of corporate shareholders in companies in a certain sector, so what should be done by the authorities is to provide concrete data before the legislate regulations.

Footnotes

Ekrem Solak, “Birleşik Krallık Ve Avrupa Birliği Hukukları Kapsamında Pay Sahibi Aktivizmi Düzenlemeleri” (2019) 2 Yeditepe Üniversitesi Hukuk Fakültesi Dergisi 127-162 p. 136 https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/2150076 accessed 10.05.2022 ↩︎

James Mancini, Anita Nyeso Common Ownership by Institutional Investors and its Impact on Competition: OECD Background Paper (2017) p. 10 https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP(2017)10/en/pdf accessed 15.05.2022 ↩︎

Solak (n 1) 137 ↩︎

Mancini, Nyeso (n 2) 11 ↩︎

Simona Frazzani, Kletia Noti, Maarten Pieter Schinkel, Jo Seldeslachts, Albert Banal Estañol, Nuria Boot, Carlo Angelici, “Barriers to Competition through Joint Ownership by Institutional Investors” (2020) European Parliament's committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs p. 18 https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2020/652708/IPOL_STU(2020)652708_EN.pdf accessed 10.05.2022 ↩︎

Daniel P. O’Brien “The Competitive Effects of Common Ownership: Ten Points on the Current State of Play” (2017) OECD Dırectorate For Fınancıal And Enterprıse Affaırs Competıtıon Commıttee p. 2 https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/WD(2017)97/en/pdf accessed 08.05.2022 ↩︎

O’Brien (n 6) 3-4 ↩︎

Mancini, Nyeso (n 2) 9 ↩︎

Common ownership and competition – UK CMA – December 2017 OECD discussion Available at https://www.slideshare.net/OECD-DAF/common-ownership-and-competition-uk-cma-december-2017-oecd-discussion ↩︎

Eric A. Posner, Fiona M. Scott Morton and E. Glen Weyl “A Proposal to Limit the Anti-Competitive Power of Institutional Investors” (2017) Antitrust Law Journal Vol. 81, No. 3, 669-728 p. 2 https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2872754 accessed 05.05.2022 ↩︎

Available at https://hbr.org/2019/02/how-big-a-problem-is-it-that-a-few-shareholders-own-stock-in-so-many-competing-companies accessed 12.05.2022 ↩︎

Solak (n 1) 132 ↩︎

Solak (n 1) 135 ↩︎

Turkish Commercial Code, Act No: 6102, Date: 13/1/2011, Publication of Official Gazette 14/2/2011/27846 ↩︎

Article 411 of the TCC ↩︎

Pelin Güven, Rekabet Hukuku Ders Kitabı (Yetkin Yayıncılık 2009) 243-244 ↩︎

Güven (n 14) 244 ↩︎

Güven (n 14) 250 ↩︎

Güven (n 14) 221-223 ↩︎

Güven (n 14) 224-225 ↩︎

Mancini, Nyeso (n 2) 6 ↩︎

Güven (n 14) 244-245 ↩︎

Güven (n 14) 245 ↩︎

Source Mancini, Nyeso (n 2) 7 ↩︎

Jo Seldeslachts, Melissa Newham and Albert Banal-Estanol “Common ownership of German companies” (2017) DIW Economic Bulletin Volume 7 https://www.diw.de/documents/publikationen/73/diw_01.c.562467.de/diw_econ_bull_2017-30.pdf accessed 04.05.2022 ↩︎

However, Jo Seldeslachts emphasized that it has an effect on competition, but that more observation and research are required for regulation. (n 25) 312 ↩︎

The largest chemical companies in Germany are BASF, Bayer and Linde. These companies are clearly competitors in the chemical industry in Germany and even around the world. It turns out that there's a major US investor called BlackRock that owns 9 of BASF, 10 of Bayer and 7 of Linde. The investor owns shares in all three companies at the same time, which he calls co-owners of the three companies. ↩︎

Competition in changing times FIW Symposium 2018 https://wayback.archive-it.org/12090/20191129215248/https:/ec.europa.eu/commission/commissioners/2014-2019/vestager/announcements/competition-changing-times-0_en ↩︎

KPMG Common Ownership and Competition (2020) page 4 Timeline https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/uk/pdf/2020/01/common-ownership-and-competition.pdf accessed 25.05.2022 ↩︎

Ulrich Schwalbe “Common Ownership and Competition – The Current State of the Debate” (2018) Journal of European Competition Law & Practice, p. 2-3 ↩︎

Mancini, Nyeso (n 2) 17 ↩︎

Mancini, Nyeso (n 2) 21 ↩︎

Mancini, Nyeso (n 2) as a whole review ↩︎

Keith Klovers, Douglas H. Ginsburg “Common Ownership: Solutions in Search of a Problem” (2019) George Mason Law & Economics Research Paper No. 18-42 https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3279612 accessed 15.05.2022 ↩︎

Bibliography

Arık B., Shareholder Actıvısm In Europe And Turkey: Is It Really Effectıve: Comparatıve Study (LLM Thesis 2016)

Aslan İ., Rekabet Hukuku (5th Edition 2017)

Azar J, Schmalz M., Tecu I., Anticompetitive Effects of Common Ownership (Journal of Finance, 73(4), 2018)

Azar J., Raina S., Schmalz M., Ultimate Ownership and Bank Competition (Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2710252 2019)

Common ownership and competition (UK CMA- OECD Discussion 2017)

Competition in changing times FIW Symposium (2018)

Frazzani S., Noti K., Schinkel M., Seldeslachts J., Estañol A., Boot N., Angelici C., Barriers to Competition through Joint Ownership by Institutional Investors (European Parliament's committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs 2020)

Güven P., Rekabet Hukuku Dersleri (Yetkin Yayıncılık 2009)

Harvard Business Review Website https://hbr.org/

He J., Huang J., Product Market Competition in a World of Cross-Ownership: Evidence from Institutional Blockholdings (Review of Financial Studies 30 2017)

Hemphill C., Kahan M., The Strategies of Anticompetitive Common Ownership Law (Yale Law Journal 1392 2020)

Hennig J., Oehmichen J., Steinberg P.,Heigermoser J., Determinants of common ownership: Exploring an information-based and a competition-based perspective in a global context (Journal of Business Research Volume 144 2022 Pages 690-702)

Kayıhan L., Rekabet Hukukunda Ortak Girişimler (Rekabet Kurumu Uzmanlık Tezi 2003)

Klovers K., Ginsburg D., Common Ownership: Solutions in Search of a Problem (George Mason Law & Economics Research Paper No. 18-42 2019)

KPMG Common Ownerhip and Competition 2020

Lewellen K., Lowry M., Does common ownership really increase firm coordination? (Journal of Financial Economics 2021)

Mancini J., Nyeso A., Common Ownership by Institutional Investors and its Impact on Competition (OECD Background Paper 2017)

O’Brien D., The Competitive Effects of Common Ownership: Ten Points on the Current State of Play (OECD Dırectorate For Fınancıal And Enterprıse Affaırs Competıtıon Commıttee 2017)

Posner E., Policy Implications of the Common Ownership Debate (University of Chicago Coase-Sandor Institute for Law & Economics Research Paper No. 922 2021)

Posner E., Scott Morton F., Weyl E., A Proposal to Limit the Anti-Competitive Power of Institutional Investors (Antitrust Law Journal Vol. 81, No. 3, 669-728 2017)

Schmalz M., Common Ownership and Competition: Facts, Misconceptions, and What to Do About It (OECD 2018)

Schmalz M., Common-Ownership Concentration and Corporate Conduct (CESifo Working Paper No. 6908 2018)

Schmalz M., Recent Studies on Common Ownership, Firm Behavior, and Market Outcomes (The Antitrust Bulletin Vol. 66/1 12–38 2021)

Schwalbe U., Common Ownership and Competition – The Current State of the Debate (Journal of European Competition Law & Practice 2018)

Seldeslachts J., Newham M.,Banal-Estanol A., Common Ownership of German Companies ( DIW Economic Bulletin Volume 7 2017)

Solak E, Birleşik Krallık Ve Avrupa Birliği Hukukları Kapsamında Pay Sahibi Aktivizmi Düzenlemeleri (Yeditepe Üniversitesi Hukuk Fakültesi Dergisi 127-162 2019)

Turkish Commercial Code (Act No: 6102, Date: 13/1/2011, Publication of Official Gazette 14/2/2011/27846)